Shiva swallowed poison to save the world. Oppenheimer ejected poison to save the world.

Confronting the Shadow: IV of the series

“There was a need for war, as if people had suffered a lack of events for a long time, coveting the ones they could only experience as television viewers. There was a desire to connect with age-old tragedy. By grace of the drabbest of all American presidents, troops would be dispatched to fight ‘the new Hitler’. Pacifists were referred back to Munich. Under the spell of media simplifications, people believed in the technological delicacy of bombs, ‘clean war’, ‘smart weapons’, and ‘surgical strikes’: ‘a civilized war,’ wrote Libération.”

Annie Ernaux, “The Years”

It was initially my intrigue with Shiva that led me down the rabbit hole of Shadow research. Before delving into the deliciously dark and compelling inconsistencies of this Hindu God, I encourage you to read my previous work on the Shadow, as this is the fourth in the series. The first of the series introduces and outlines my approach to “the shadow self”. The second tackles the “shadow” of the West through the lens of Edward Said’s Orientalism. The third essay attempts to dismantle the antagonistic and controversial topic of "evil”.

Click here for the introduction: “Confronting the Shadow Self”.

Here for the second: “Why the West doesn’t want to meet its shadow self”

And here for the third: “Does Evil Exist?”

Who is Shiva?

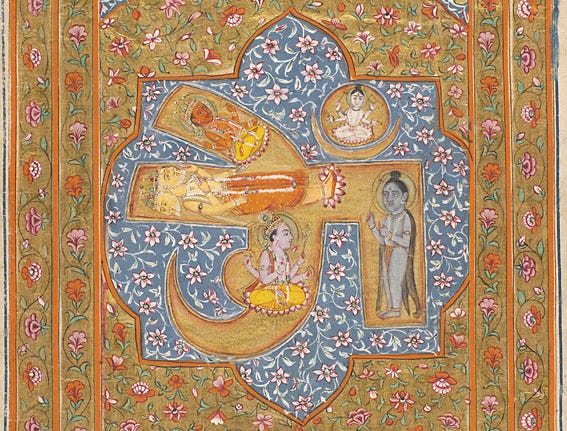

Shiva is one of the principal deities in Hinduism. He is one of the three forms of “The Trimurti”, which is the trinity of supreme divinity including Brahma, the creator, Vishnu, the preserver, and Shiva, the destroyer.

“Beautiful One, who knows no death,

knows no decay and has no form”

Devotional poem to Shiva by Akka Mahadevi

Shiva’s name translates as, “the auspicious one”, but he is also the destroyer, the final part of the Trimurti that enables the destruction of the universe for it to come full circle again. Within Shiva are the paradoxical qualities of creation and destruction.

It fascinates me that a destructive god is an integrated and necessary part of spiritual worship in Hinduism. Shiva is also the leader of evil spirits, ghosts, and thieves. Yet Shiva is not vengeful—he represents pleasure, dancing, music, benevolence, and joy. He guides people to practice quiet contemplation and meditation as a means to find happiness.

Archetypally, it reminds me of the pagan god Pan, who symbolised fertility, spring, merriment, and wild, excessive dancing, counterbalanced by long stretches of rest and contemplation. If Pan’s rest was interrupted, his deafening scream would let off a cycle of chaos and destruction in the otherwise idyllic pastoral setting in which he roamed. In Hindu mythology, the universe collapses and regenerates every 2,160,000,000 years. Shiva is a crucial part of this.

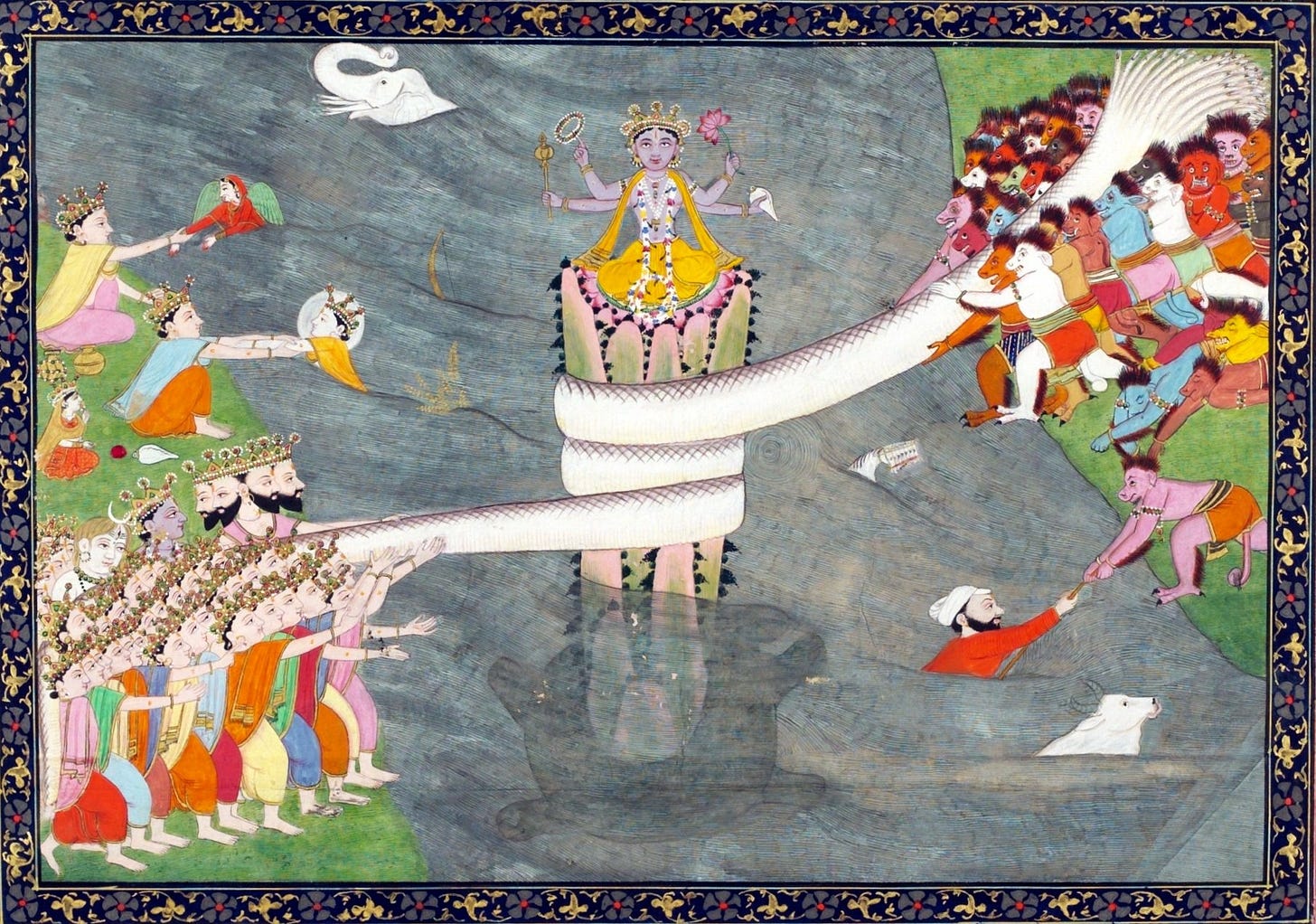

In one of the myths about Shiva, the god swallows poison to save the world. The deities had been weakened after a deluge caused them to lose their powerful treasures to the ocean. To retrieve the treasures, the gods created an alliance with the demons, asking for their assistance to wrap the great serpent, Vasuki, around Mount Mandhara to churn up the ocean. In doing so, they hoped to reclaim the coveted objects they had lost, and regain their prestige as gods.

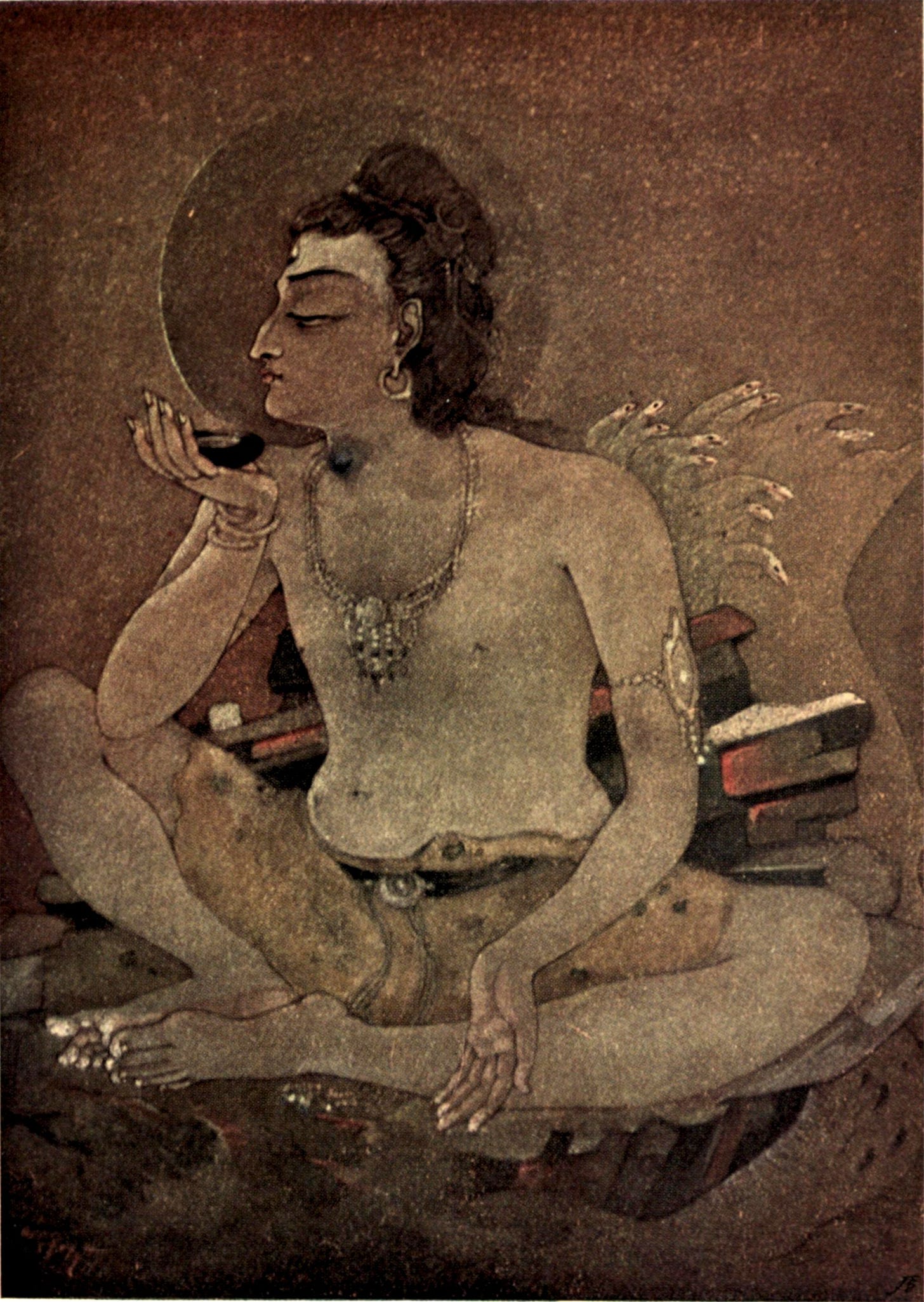

They struggled with the task as a highly venomous poison was continuously ejected from Vasuki’s mouth. To deter the destructive path of the poison, Shiva drank it, holding it in his throat so that it would not reach his stomach where three worlds dwelled. Shiva’s act of self-sacrifice turned his throat blue, and because of this He is often depicted with a blue throat and is also known as “the blue-throated one”.

This is a tale of true resilience. Some sources say that the churning of the ocean took place over a thousand years before any lost treasures were recovered. Interestingly, across the cultures, almost every end-of-the-world, creation myth features a large serpent and a churning sea. More of that in my next piece, which delves into sea serpents (keep tuned if this interests you).

Learning about Shiva sparked off an internal revolution that helped me reconsider how I perceive existence. It disintegrated the concepts of Christian moralism that I still held unconsciously. I had never correlated ecstasy, or chaos, with quiet meditation. In the figures of Pan and Shiva, these two states are interchangeable. They are figures that represent happiness, but also destruction. In my Westernised view of the world, these concepts were diametrically opposed. Excess and joy were the enemies of a productive, puritanical work ethic: ideas that arguably lay the foundations of Western culture to this day.

Within Western ideology, destruction and death can only be related to evil and suffering. Yet, if we think about it deeply, it is a truism that contravenes laws of nature. We only have to look at the dying plants of winter renewed in spring to understand this. Western Christian ideology covets a fear of death; a nonsensical desire to live forever; deplores sickness, yet also rest, and even the more instinctive aspects of pleasure-seeking. Pleasure must instead be found in productive and constructive activities.

Is Destruction Always Negative?

From the perspective of my current, early 21st-century Western European privilege—and as astutely observed in Annie Arneaux’s “The Years”—chaos and destruction are phenomena mostly observed on TV screens, relegated to occurrences happening “elsewhere”.

Growing up in the UK, I have thus far been untouched by catastrophic cyclones, floods, and earthquakes. Some of my ancestors would have seen death and destruction on a mass scale almost a century ago during the air raids and bombs dropped on Glasgow during the Second World War. A direct descendant was assassinated by the British army during the 1916 uprising against the British occupation of Ireland. The ripples of those disasters continue to hit us a century on.

Currently, our news feeds are exploding with the horror of destruction in Gaza, a geopolitical situation that has been woefully mismanaged at an international level. The disastrous division of territory drawn up during the Balfour Declaration and the subsequent retreat of British forces in Palestine has caused decades of violence, displaced Palestinians, and illegal occupation. It is a particularly poignant example of how ignoring the shadow can become a disaster so astronomical in scale it seems irresolvable.

For precisely these considerations, it appears problematic to laud the concept of chaos and destruction from my current position of relative safety. My associates and I watch in horror, feeling powerless, as “far away” countries such as Palestine, Sudan, and Ukraine (the latter not so far away) suffer the effects of extreme political upheaval and war. Prayers, money, and convoys are sent. Many choose to ignore the situation, getting on with their busy lives.

Yet, there is a palpable anxiety rippling through Europe. A “pandemic” of mental health problems has been attributed to living costs and overuse of social media, but I am not convinced that these are the principal causes. As observed by a friend I was speaking to recently, this collective anxiety possibly stems from an underlying sense that all this destruction, seemingly so “far away”, is closer than we imagine. Necessarily, we are all connected, whether we like it or not.

Like the shadow—and these global wars are physical apparitions of a collective global shadow—the chaos and destruction we are “observing” are undeniably integrated into our own lives. It is my opinion that we cannot truly disconnect, nor forget that these occurrences are happening, nor feel assured by a certainty of safety whilst these upheavals continue to rage. We are the other side of the coin, and we cannot remain untouched by the ravages of war.

Vishnu says destroy! Did the Western interpretation of the Bhagavad Gita lead to nuclear warfare?

If you’re not born into the tradition, it is difficult to fully comprehend the structure and ideology of Hinduism, its mythology, and its Gods. I have read sections of the Bhagavad Gita and the Upanishads but, due to their sheer density, had to drastically limit how far I reached into Hindu religious scriptures (for now). It is a vast and complex area of study. Therefore, I write this fully disclosing, and acknowledging, my ignorance of the depth and rich integrity of the Hindu tradition. My basic knowledge of Shiva and other Hindu Gods was birthed in the curious delight of discovering ideas outside of the oppressive doctrine of my monotheistic forebears.

Around the time that I began to research these ideas there was a flurry of excitement around the release of the 2023 Oppenheimer biopic. This blockbuster centred around American scientist, J Robert Oppenheimer, who was drafted into head Project Manhattan’s secret weapon laboratory in 1942. The US had entered the Second World War intending to end it definitively. The project, also known as Los Alamos, was responsible for the birth of today’s most terrifying monster – move over Leviathan! – the atomic bomb.

One of today’s most feared threats is nuclear warfare, looming into the public consciousness after two bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan in 1945. Between 129,000 and 226,000 people were killed, almost instantaneously, thus signalling a spectacularly horrific ending to The Second World War.

Oppenheimer, known as “the father of the atomic bomb”, was variously lauded and vilified for his part in the invention of a weapon that changed the course of history. Oppenheimer later admitted that his participation in the atomic bomb creation had been a Faustian pact. In creating a weapon that could end all wars, we have arguably been forced into a psychic state of war ever since. Nuclear warfare has instilled in us the ever-present threat of total annihilation.

Like Frankenstein, who abandons and later attempts to murder his monster, Oppenheimer had regrets and spent much of the rest of his life campaigning for stringent global controls over nuclear weapons. Oppenheimer also fell afoul of the political machine he had become embroiled in. Oppenheimer spent the latter part of his career defending himself against accusations of being a Communist sympathiser. He had antagonised too many large political players, and as a result, was stripped of his prestigious position.

I was excited to see the film. I had hoped it would deliver a strong but knotty treatise on the futility of nuclear warfare and its tyranny over the contemporary psyche. Perhaps there would be self-reflective meditations on the US and its role as a foreboding intimidator on the world’s stage. The mask of the US would slip – the heroes who save the day in the zombie movies would give up the ghost. We would see that one of the great forces of chaos and destruction was not Godzilla but the US itself (and its trusty court jester—the UK). The US was Shiva without the Trimurti: the great destroyer without fruitful post-creation or preservation.

Disappointingly these issues were not confronted in the film, bar a shoddy, abstract scene reconstructing the destruction of the atomic bomb in Japan whilst Oppenheimer delivers his victory speech. It was akin to a shrug, half-grimace, a “sorry, my bad”. Aside from this, the film was schmaltzy and excessively long. The “what-have-we-done?” moment following the aftermath of the bombing in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was anticlimactic. After “the main event”, the film segued into boring court case scenes of angry men avenging the success of Oppenheimer; tempered by juicy trysts with Oppenheimer’s mentally ill Communist lover, or him as the “long-suffering” husband in scenes with his “hysterical”, alcoholic wife.

Oppenheimer was fascinated by Hinduism and therefore studied Sanskrit. His favourite and oft-quoted text was the Bhagavad Gita. There is a famous and rather electric moment, canonised on Youtube, where he quotes from the Bhagavad Gita in a live TV broadcast in 1965 whilst reflecting on the atomic bomb. The excerpt is a quote from Lord Vishnu who is urging Prince Arjuna, losing heart as he goes into battle, to fight on and achieve victory. Vishnu reiterates that He is a Supreme God, therefore it has already been decided by Him, as ruler of time, that the prince will win and obliterate the opposing force. Arjuna must go ahead and do what fate has portended.

In Oppenheimer’s words, the quote is:

“Vishnu is trying to persuade the prince that he should do his duty: ‘Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds’. I suppose we all thought that one way or another.”

Oppenheimer appears to suggest that he had no agency in the matter of the atomic bomb, and that he had only to do his duty. The result was—as he later admitted to an irate Harry S. Truman—that he had blood on his hands. Whether one agrees or disagrees with Oppenheimer’s esoteric claim, the fact that this moment has resurfaced in the public psyche is interesting.

In the film, Oppenheimer is depicted as directly reading it out from the Bhagavad Gita, simultaneously translating it from Sanskrit to his impressed lover. I have mused upon why Christopher Nolan, the film’s director, made this artistic choice. I imagine he supposed it would be more sensational to deliver the famous quote after a steamy sex scene, in lieu of a dry television interview.

The film encourages us to admire Oppenheimer—freely able to translate Sanskrit to his young lover post-coitus—but the quote in its true context tells another story. Reportedly, for Oppenheimer, Hindu scripture was more of a compelling mysticism than a religion he practiced. On live American TV, Oppenheimer reclaims the scripture to justify the West’s warring actions, or more accurately, to frame these actions as the inevitable course. And that is the prevailing dogma of today in the West, that though the bombing of Japan was deeply regrettable, it was the only solution to end the war.

It is disappointing that the highest-grossing biopic ever made was a weak, dithery apologist stance on the atomic bomb. Was it even that? Or just another “he was a complex and controversial man” biopic, where we are supposed to admire the chutzpah of a no-doubt highly intelligent, but also highly privileged person? Was the atomic bomb the poison needed to save the world? Or merely the precursor to perpetual warring throughout the globe in its wake?

Reporting on the conflict in Ukraine, VICE announced this year that “Nuclear War anxiety is back”. The shadow cast by the nuclear threat shows no signs of shifting. Will the oceans churn for another few thousand years? Will a new version of Shiva arrive to swallow the poison?

In the Hindu scriptures, it is declared that an earth such as ours is dissolved for one of two reasons: the inhabitants become either completely good or completely evil. We all know, and the scientists agree, that this world will end.

The question is, do we accept its end as a thing of beauty, and like Shiva, look at destruction in conjunction with joy, and renewal; a final act of noble self-sacrifice? Or do we continue to observe the cold-blooded murder of innocent human beings, and the destruction of our beautiful planet as “a necessary evil” to secure one’s survival?

I know which route I’d opt for.

And if it was a toss-up between worship of the blue-throated one or Oppenheimer, little doubt remains in my mind.

Every thing that is any where, is produced from and subsists in space. It is always all in all things, which are contained as particles in it. Such is the pure vacuous space of the Divine understanding, that like an ocean of light, contains these innumerable worlds, which like the countless waves of the sea, are revolving for ever in it.

There are many other large worlds, rolling through the immense space of vacuum, as the giddy goblins of Yakshas revel about in the dark and dismal deserts and forests, unseen by others.