We think of tears as being part of a solitary activity. Yet traditionally crying was a public act.

Archetypally it is women that are permitted to cry publicly. In Mexican folklore, La Llorona was a vengeful ghost who wandered near bodies of water to mourn the children that she had killed in a jealous rage to spite her husband. In Southern Europe they parade statues of the crying mother of God during Holy Week. People flock to see her, touching and kissing the large statue as it is perilously carried through narrow streets. Our Lady of the Sorrows is often depicted pierced in the heart by seven swords, representing her seven great sorrows.

Have you ever cried so much you had no idea what you were weeping for?

Have you ever cried on behalf of someone else?

I once met a special person. We bonded over poetry, the Spanish language and being away from loved ones. We talked about the difficulty of saying goodbye; how to miss people. Through these conversations I realised that I’d taught myself to stop missing people. At some point I even stopped saying goodbye to the people that I had shared a profound connection with. I reasoned to myself that saying goodbye was too final. You would never know if you would see that person again, or not. I never had to let go.

We worked in a bookshop. I always knew my time there was temporary. I was moving to another country again. On my last day of working at the bookshop I inexplicably broke down, crying inconsolably like a child. My friend removed me from the shopfloor and stationed me in a cupboard. They regarded my weeping without fear. My body had gone to jelly. I should have felt embarrassed, but I didn’t. I realised I was finally crying for all the goodbyes I had never said. And I realised I was crying for this person too.

Psychotherapy articles on the internet say that you might have a tendency to cry on the behalf of others if you are particularly sensitive. Something I learned about the Spanish language is that describing someone as “sensitive” is a positively glowing review. In the English language it is practically an insult. This particular article warns about the danger of taking on the emotions of others, recommending “dissociation” against negative emotions. The problem here is that societally sadness is often considered “negative”, when really it might be a natural response to a difficult situation.

I can think of nothing worse for one’s mental health than learning how to dissociate from your emotions. Of course, a crying workforce is not good for the capitalist economy. Wearing tears like jewels on your face is embarrassing and unproductive. Only statues are permitted to do so.

The Irish had a practice known as “keening”, where women would publicly lament at the wake of the deceased. It was exaggerated and bawdy. It terrified English Renaissance poet Edmund Spenser, who believed that the Irish were savages. The art of keening has died out in recent centuries, but it was practised in European, Judaic and Arab cultures from Ancient Greek and Roman times. It is still practised today in the Middle East and parts of Africa.

Why Weep?

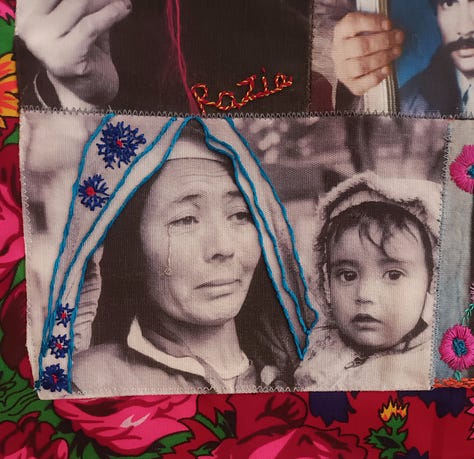

Recently I saw an exhibition at Street Level Photoworks in Glasgow. It was showcasing the works of Jenny Matthews, an artist and war photographer. The exhibition had thirty-five portraits of Afghan women with embroidery “obliterating” their features. The series was to commemorate the Taliban retaking control of Afghanistan in August 2021 and to highlight the subsequent negative effect on the lives of Afghan women and girls. The exhibition also showcased Matthews’s work on the current crisis in Sudan and new images from Gaza.

The embroidery of flowers over the faces of women performing ordinary acts, such as sewing, gave them a saintly, mystical quality. One tapestry featuring an Afghan woman crying, her tear delineated by stitching, really drew my eye. Another image of a weeping elderly woman in war-torn Bosnia also stood out to me. It didn’t have any embroidery or embellishments added. It was simply the woman’s face. There is something about a weeping face, wet and crumpled in on itself, that transmits so deeply a person’s inner plight. Indeed, even the fate of their country.

The world appears to be crumbling around us.

Owing to social media, we have an increasingly clearer picture of the violence of war and apartheid devastating the globe as I write, and as you read. Public weeping is not so much a ritual, but a huge klaxon alerting us to the problems in today’s world. We could continue with our dissociative techniques, maintaining ourselves as a muted and focused workforce. Or, could we afford to stop a moment and cry with the weeping faces on our screens? Lament the unequivocal signs of climate destruction that can be seen with the naked eye?

I do not propose that we overwhelm ourselves with the constant influx of media images and videos. In fact, I make a conscious choice not to do this. Yet I resist the urge to dissociate; extricate myself from emotions, or suppress tears at the suffering of others. In Hannah Arendt’s writings on free will, she talks about how “self-control”, or a lack of emotional display is “the hallmark of the aristocracy”. An aspiration to be part of the higher echelons of society has instilled in us the idea that restricting emotions proves us to be more worthy. Unfortunately, short of marrying into the aristocracy, or plundering land with the same gusto as their ancestors did, if you aren’t born into it, you will never be an aristocrat. Emotional disorder is then the hallmark of the lower classes, who are at the front line of economic depressions, war and violence.

It could be argued that crying in the face of devastation is redundant. But I invoke its power. Religious or not, why do the faces of the crying Madonnas move us so deeply? Can these sentiments be echoed in inanimate objects; the spaces around us?

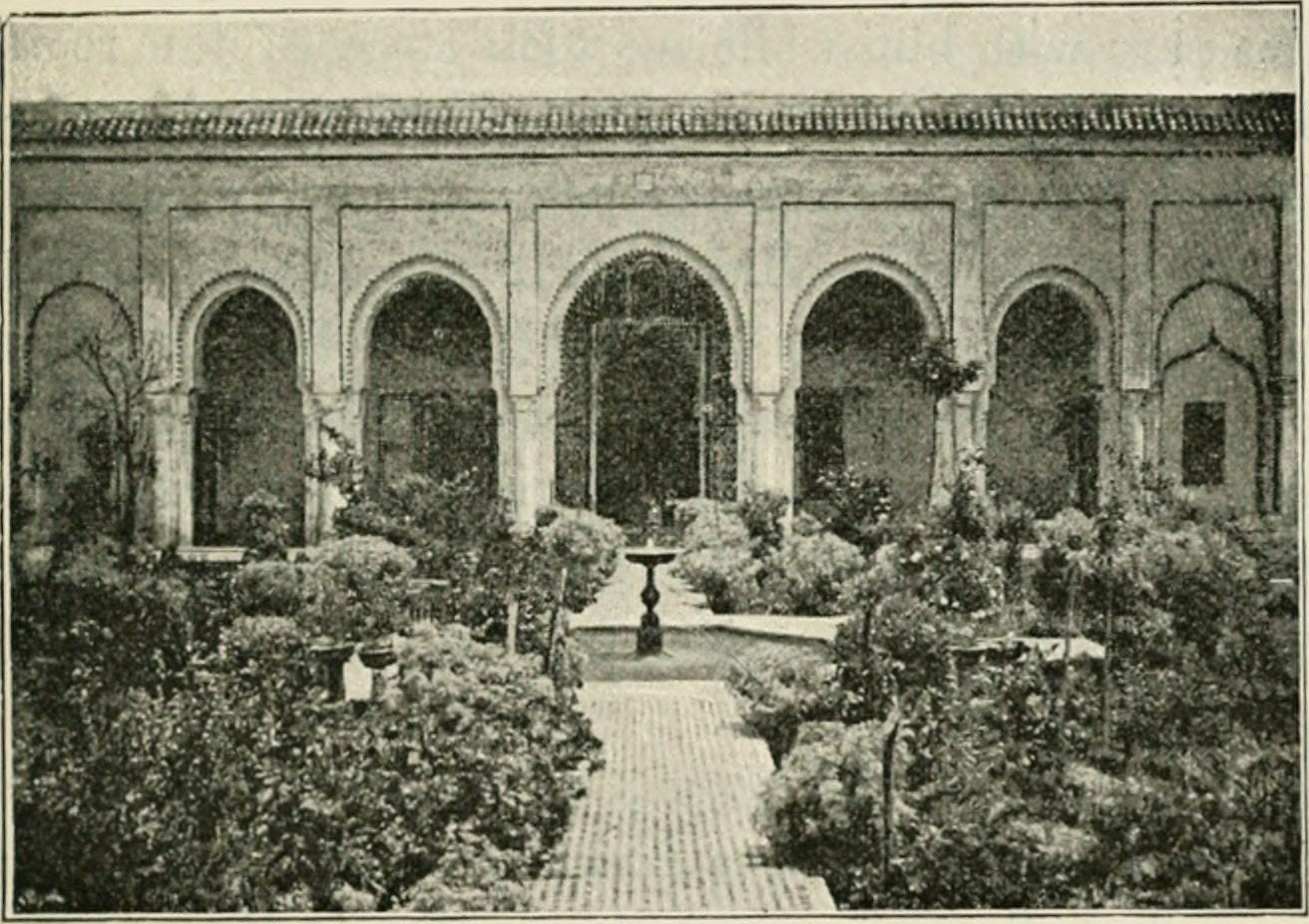

In my article, Does the City Have a Sound, I wrote about hearing the roaring noise of water fountains at periodic times of the day in Andalusia whilst living there.

In fourteenth century Granada, there was a connection between the water cycles of the fountain, the Islamic call to prayer in the morning, and the Christian Vespers of the afternoon. The violent gush of an Andalusian fountain puts one in mind of weeping. Religious ceremonies invite us to feel sorrow with others. Not to contain the grief, but let it pour out. Watching these jets of water leap with wild abandon gives one a sense of release. This is particularly well received during Andalusia’s long months of drought, where one longs for just a drop of rain.

Now back in the old country (Scotland), I wander through the Trossachs and am grateful to be subjected to the seemingly never-ending rain, and the abundance of rivers that boldly surge through forests and glens. I noted, during a time of personal sorrow, that the diverse consistencies of flowing water, The Endrick, or Allander Water, somewhat eased my suffering.

Boys Don’t Cry

There is, of course, a distinct lack of weeping masculine archetypes. I was struck by the weeping image of the Fool in Caroline Myss’s archetype cards. The sad clown has certainly made its way into the public psyche. Krusty the clown’s impassioned lament on the Simpsons, “Send in the clowns”, springs to mind. The Fool is the one who wears his heart and vulnerability on his sleeve. I write, in part, about this in my article on the Fool archetype.

I was also struck by the myth of the Ancient Egyptian Sun God Ra, whose tears consisted of honey, transforming into bees when they hit the ground. Bees, and the honey they produced were sacred to Ancient Egyptians. They were medicinal, and we can also recognise these health giving properties in salt tears. Scientific research into crying reveals that it releases oxytocin and endogenous opioids, also known as endorphins. Endorphins help ease both physical and emotional pain.

Recently, as I walked through Glasgow city centre, I was struck by the ubiquitous sight of men clutching cans of beer in the middle of the day, shouting and swearing at passers by. We tend to shun these types of men. Would we be kinder to them if their howls were weeping, and not battle cries? I imagine so.

My dad sent me a picture of a stone Christ revealing his wounds on the side of a Cathedral in Vienna. I tartly replied to him, “that’s a good start”. I don’t intend for this to become a treatise on organised religion. Yet I concede that there is a power in the gruesome imagery of early Christianity that hadn’t yet distanced itself from paganism and its less sanitised conception of humanity.

We must show our wounds. We must cry together. We must reveal our pain. If not, how can it be healed?

James Hillman wrote:

“even the favourite dictum of reflective psychology–a psychology which has consciousness rather than love as its main goal–”Know thyself,” will be insufficient for a creative psychology. Not “Know thyself” through reflection, but “Reveal thyself,” which is the same as the commandment to love, since nowhere are we more revealed than in our loving.”

Tears are a collective wound, or even a collective armour. We cry for ourselves. We cry for each other. Crying is prayer. Libations are poured to great, powerful gods to ward off evil being done to us. We cry for our friends and partners when they cannot cry for themselves. We cry for oppressed people who are unable to cry because they are fighting to survive.

If we lose this ability, we lose the connection to ourselves and to others. This is not to shame those who cannot cry, but to remind them that there are others who are willing to cry with and for them.

"We, from the distance,

fill up with tears,

the sea, the earth, and the sky.

But, crying out, they are

washed away by the wind,

and the weeping woman

remains dry-eyed, desolate."

Pablo Neruda

If you would like me to shed a tear for you, please buy me a coffee or two.

Thank you!