The Spectres Still Haunting Europe

Confronting the Shadow V: Why do we still love ghost stories? Why are some monsters more popular than others?

In my last piece, about Shiva, and Oppenheimer, I wrote about how the shadow of the nuclear arms race continues to loom over us. We notice that conflict unresolved, or evil and harm, unchecked, at a minuscule and monumental scale, doesn’t disappear. It becomes the shadow, the opposing force sinking its claws into everything good we try to do subsequently. Considering this, it doesn’t surprise me that even with the development of technology and science, our obsession with the supernatural, spirituality, and the occult has shown no signs of wavering.

Do we find comfort in paranormal phenomena? Is a vampire or ghost a less terrifying prospect than a nuclear attack from Russia or China, or even a vaccine?

Where do ghost stories have a place in today’s paranormal contemporary landscape? Judging by popular culture they are as thriving as ever. In 2023, one of the most talked-about TV shows in the UK was the BBC documentary series, Uncanny, presented by the pixie-like, green-eyed Danny Robbins investigating real-life paranormal stories. Horror and Gothic are genres unshakeable in their popularity. You’re either into it or you’re not. Along with the Twilight franchise, and countless other films and books, the Vampire is a particularly popular ghoul of choice. It was the early nineteenth century that first embedded this cult monster into Western society.

We could chart this back to the short story, The Vampyre, written in 1819 by Byron’s physician, John William Polidori. The introduction of The Oxford Classic’s edition of “The Vampyre and Other Tales of the Macabre” (1997) explains:

“The story had made an indelible impression on the imagination of Europe, and Polidori had succeeded however inadvertently, in founding the entire modern tradition of vampire fiction.”

Subsequently, the figure of the vampire has been canonised and cemented as a horror stalwart after the success of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, still a Gothic fiction favourite to this day.

The circumstances surrounding The Vampyre story, and its influence on literature, TV, and film, are more interesting, in my opinion, than the story itself. Polidori was a young doctor, and against the advice of his parents, accompanied Lord Byron as a travel companion to Switzerland. During this fateful trip, along with Percey Bysse Shelley and Mary Shelley, the entourage famously challenged each other to write a ghost story. Fascinatingly, it was this challenge that birthed the beginnings of Shelley’s cult novel, Frankenstein.

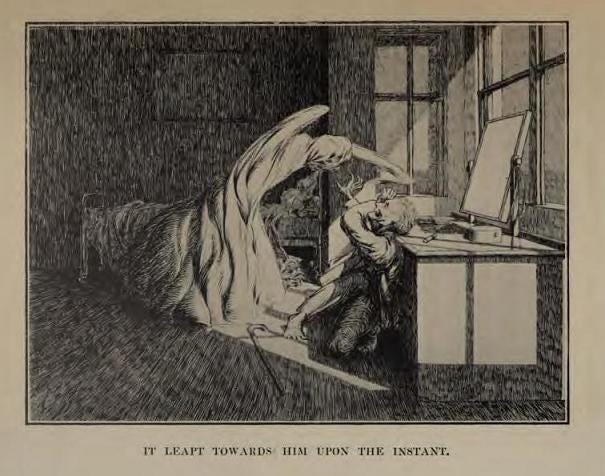

It was also the instigator for Polidori’s The Vampyre, originally published under the name of Byron, and later corrected. The tale is about an aristocratic vampire who seizes upon the affections of fair, young ladies to keep himself alive. The narrator is his young travel companion, who, as he watches the horrific series of events unfold, becomes severely traumatised. The protagonist, haunted by the dark deeds of the vampire, eventually dies, unhinged and raving.

The mirroring of Polidori’s own story is bizarre. There was a breakdown in relations between Byron and Polidori, leading to Polidori’s dismissal. A brief googling of Polidori’s life reveals that he died by suicide after addictions to gambling and boozing. It would be simplistic to say that he was haunted by the spectre of Byron. Yet the fact that his popular story was always attributed to his patron could have led to some deep-harboured resentment. The introduction in the aforementioned copy of the book talks about Byron’s entourage being sexually liberal, and this may have been shocking to any outsider during the Victorian era. Who knows if the sensibilities of the young physician, Polidori, were disturbed by the sexual hedonism of Byron’s harem, while Byron could have been perceived as the immoral, vampiric ringleader.

According to the introduction of this Oxford Classic’s edition, it was Polidori who “set in motion the glorious career of the aristocratic vampire”. Its origins in Eastern European folklore often characterised vampires as peasants living in isolated villages or towns. In Bram Stoker’s Dracula, published decades later in 1897, Count Dracula owns a castle and estate in deepest Romania and is believed to be based on the 15th-century Wallachian prince, Vlad the Impaler.

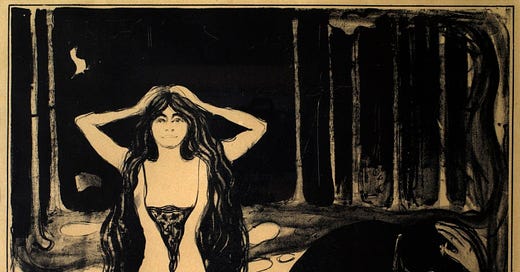

The 19th century was an era that marked a growing unease with feudalism. Events such as the French Revolution unequivocally rejected the rule of the aristocratic landowners and the divine right of kings. Characteristically, the revolution didn’t reach the UK, and to this day aristocrats and landowners continue a quiet type of feudalism across the kingdom. Yet the aristocratic Vampire looms large in our psyche; an immoral creature who continually sucks the lifeblood of the people. We still live with the spectre of Count Dracula, a nobleman who stole the babies of his subjects to prolong his immortality.

How very British, to observe the unfair division of resources, quietly ignoring it while the deep-seated shadow of resentment grows inside. The anger must go somewhere, and politicians orchestrate fear about the scarcity of jobs and resources, lancing the blame at incomers and immigrants. Incidentally, this is a theme in the book that Dracula fanatics have conjectured about, Dracula as this dark, evil force from deepest Romania invading the shores of virtuous England. Lucy Westenra, sweet, pretty, and guileless, is Dracula’s first victim after his arrival. We watch the bloom of her youth fade as she loses her innocence and becomes the voluptuously immoral “Blooper Lady”, enticing local children to their untimely deaths.

It reminds me of something Hannah Arendt wrote about free will and the aristocratic outlook. Arendt posits that in ancient societies the concept of “freedom” was the outcome of an effort created in conjunction with others, the body politic of people. Whereas:

“The self-control, or alternatively, the conviction that self-control alone justifies the exercise of authority, has remained the hallmark of the aristocratic outlook to this very day.”

The aristocracy could attain freedom without the effort of collaborating due to their access to money and land. They represent the ultimate in self-control; power is held through self-interested actions. Self-control and individualism have become the ideals of aspirational thought. The aristocratic vampire living vividly in today’s public imagination epitomises individualistic aspirations. The aristocratic vampire does not need a community, only the lifeblood of his lowly cohorts. Our belief in this figure is a resigned acceptance. It is a mutual interdependence but without love or life force. The life force is drained by survival. The spectre is still haunting Europe.

Ghost Stories and Monsters in the Modern Psyche

During a short, but delightful tenure working at Waterstones in London’s Bloomsbury, I was lucky enough to be sent a pre-published copy of Jeannette Winterson’s collection of ghost stories, Night Side of the River (2023). In her introduction, Winterson references the rise in the popularity of the ghost story genre in Europe during the nineteenth century, referencing writer Nathaniel Hawthorne. Hawthorne was a puritanical writer of “dark romanticism”, and a descendant of a prominent Salem witch trial judge. Hawthorne wrote cautionary tales on what he felt was an inherent sin and evil in humanity. Winterson muses that Hawthorne,

“built into his stories the psychic fractures and guilty disturbances peculiar to the pioneering spirit that is haunted by very different spirits. The question is: Are such hauntings from the outside or inside?”

A pertinent question, provoking me to wonder why certain ghouls and monsters, such as the vampire, inspire us so much, or why specific monsters become a hallmark of a certain place or time.

The nineteenth century saw a frenzy of sea serpent sightings, which have since dwindled. Were sea serpents endangered by the recent glut of large cruise ships of pensioners marauding the ocean, or the aggressive trawlers scooping up and discarding the bodies of un-marketable fish? When sea serpent sightings were at their height, the activity of the sea represented a particularly uneasy moment in history.

There was the fear of invasion (France and Napoleon); later the fear of revolutionary activities spreading through Europe (France again); and also the fear of migration. These fears endure, but they were heightened in an era where so much activity, trade, invasions, and wars were happening at sea. Nowadays, we are more anxious about the sky, waiting for it to fall onto us. Sea serpents have been replaced by UFOs, and considering the secret activities of nations preparing for nuclear war these worries are not entirely unfounded.

On Victorian Web, a treasure trove of essays about literature and culture in the Victorian era, Simon Cooke posits:

“Sea-serpents are no longer popular and no longer seen. The fact that the great waters of the world are crowded with vessels that no longer report such encounters reaffirms the beasts’ mythological status. Indeed, the sea-serpent discourse is yet another example of some of the absurd beliefs of the age – such as phrenology and physiognomy – which now seem startlingly naïve or just superstitious, the residue of a more primitive, pre-scientific mentality.”

From a contemporary perspective, belief in sea serpents may seem absurd, relating to a “pre-scientific mentality”. Yet we cannot forget the more bizarre theories that have circulated in recent years, such as Qanon’s “Pizzagate”. Or Bill Gates’s supposed collusion with other global elites to microchip the population with vaccines, to then sell our data. It’s not that I do not believe rich people or corporations wouldn’t want to mine and sell our data. Quite the contrary. The microchip would be an unnecessary expense, since we already give our data willingly and for free through our smartphones, and other such activity.

An amusing tweet doing the rounds last year quipped:

“It’s fun that some folks think a secret group of rich people control everything instead of the widely known group of rich people that control everything.”

Therefore, while Simon Cooke suggests that sightings of sea serpents in the Victorian age were the outcome of “a more primitive, pre-scientific mentality”, I don’t believe much has changed in terms of wild, unsubstantiated theories peddled and spread. Undoubtedly, there is some comfort in creating bizarre and far-fetched theories. We enjoy stories.

For example, I thoroughly enjoyed the 2006 film, The Lives of Others, which was about a Stasi agent tapping into and surveilling the home of a blacklisted playwright and his girlfriend. We see the agent get increasingly enthralled by the meaningless drama of their everyday lives. He falls in love with them. The film won a BAFTA and a Golden Globe, capturing the hearts of international audiences. My theory about the film's popularity is that it represented a humane portrait of espionage in a time when surveillance is increasingly depersonalised. We have become nostalgic about surveillance in a bygone, analogic age.

Perhaps being haunted by a ghost, or Stasi agent, is infinitely more appealing than the idea that we are faceless data and numbers being collated by AI technology. It doesn’t matter to the machine who we are anymore, whether we’re “breaking the rules” or not. All that matters is that the appropriate data is collected and that our tastes, ideologies, and marketing profiles are slotted into the algorithm.

Reflecting the reality of the age, Jeanette Winterson’s Night Side of the River brings ghost stories into the 21st century. The book is split into three themes, which are “devices”, “places” and “people”. The first part of the collection is dedicated to “devices”, exploring where the paranormal might intersect with technology and AI.

Generally, as a writer, I have refused to join the moral panic about AI. I have an idealistic—perhaps arrogant—belief that a machine couldn’t possibly replace a good writer. AI is an inevitable outcome of the way that we expect people to work, in a society motivated by greed, and the exponential accumulation of wealth. I don’t regard AI as a force of evil but as a symptom of a sick age. Therefore, I was doubtful that Winterson’s AI-themed ghost stories would spook me.

Yet something about the story, “Ghost in the Machine”, hit me hard. The tale ends with the female protagonist exchanging her real life for a fantasy after falling in love with a sophisticated virtual reality program called Ariel. In the real world, she is haunted by the ghost of her deceased husband. She isn't even frightened. I suppose that the normalcy of leaving the physical realm, and her increasingly frequent visits to virtual reality reduces the shock factor. If the membrane between physical and virtual reality is so permeable, why not the separation between that of the living and the dead? The haunting merely becomes an extension of her unhealthy relationship with her dead husband:

“He’s hoping I will die of pneumonia, then we can spend eternity fighting each other, but I’m going to get better to spite him. Hate is a powerful reason to live.”

Finally (spoiler alert), she cuts her own life short, persuaded by her virtual lover to end her days in a digital love paradise as her “top-end avatar”. The final lines of the tale bring shivers up my spine. When she dies, floating away from the seedy motel she has overdosed in, she muses:

“Another world and I am here. Another world where I made the right choice.

Another world where I don’t have to turn away from love.”

It is tragic, but who’s to say that the “real” life the woman had, living in a flat haunted by her dead, detested husband, is any better than the ideal virtual life she trusts she will have after corporeal death? Nevertheless, what truly chills me about Winterson’s story is the idea that the protagonist is continually “turning away from love” in her real life, and is only able to embrace it through death, with the promise of a fulfilling afterlife. She believes that she is unable to experience love in her corporeal, living self.

Therein lies the danger of capitalism, religion, or addiction to virtual reality: they offer us an idealised form of loving that we can escape to, and we refuse to do the difficult work of loving in the reality we are present in. In this story, Winterson truly encapsulates the haunting of the contemporary age.

Another tale in the collection that stood out to me was “No Ghost Ghost Story”, a story about a man called Simon who is almost-haunted by his recently deceased partner, William. In his grief, Simon goes to a medium, who fails to make a connection between him, a man of science, and his equally sceptical phantasmal partner. Simon imagines William saying to him, “‘There is no haunted house… I am not here. Don’t step out towards death like it’s a speeding car.’” Even Simon’s own memory of his partner does not permit him to depart from “reality”, or what is perceived as being “here”; logical; corporeal. Simon perceives contacting the dead as a hastening towards his own death.

This, for me, begged the question, and it is one I would want to extend to all these “people of logic, and science”: When was it that we decided that “corporeality”, or what is seen by the naked eye was an a priori fact of existence? That we can confirm existence through the ability to perceive a body or thing is not necessarily logical. There are many things we do not see with the naked eye that we know exist, through science. And we would do well to remember that science within itself is not a fail-safe truth, but a methodology used to disprove or prove facts. I also challenge the assumption that contacting “the other realm” would negate the fact of living. Contacting the dead does not necessarily underpin a wish to die.

Despite being a “man of science” Simon is frustrated that he is not haunted by his deceased partner. We also get some perspective from the ghost, William, who attempts to reach Simon from the other world but is unable to make definitive contact. Even William, as the haunter, doubts his ability to reach his partner. Indeed, William appears to be more concerned about Simon’s reputation than establishing contact: “Friends are concerned. Is he losing his mind? I am dead – rot has made a meal of my body.” He reminds himself that his body has stopped living, his heart no longer beats, and therefore he no longer exists. William doubts his very own ghostness.

Yet they are both somehow present with the other: one wanting to be haunted, the other wanting to enact the haunting, but unable to permit it to happen, because of propriety, because of logic. Ultimately, William’s half-hearted attempts to make contact are not totally unsuccessful. Simon confides to his friends that he fancies he can feel the presence of William, but they dismiss him, attributing it to a kind of grief hysteria. It is sad and frustrating to witness, as a reader. Ultimately Winterson relieves us, ending with a tender portrait of the couple, separated by life and death, an almost-haunting, but in the bounds of reasonability, or rationality. As narrated by “almost-haunter” William:

“Later, when it’s time for bed, Simon goes upstairs wearing me like a safety net. I am fastened around him. I won’t let him fall… I close his eyes gently, as gently as he closed mine. I cover him with the last of me, and I love him, and he sleeps.”

This touching image allows us to understand haunting as a loving, nurturing presence, and not the evil intrusion so often depicted in ghost stories. It is a plausible depiction of the separation between life and death that bereaved people might experience. When a dear one has departed, we long for them to return; and a haunting will permit that, almost defying the reality of death. Yet most of us will have to suffice with a half-haunting; the memory and the presence of the deceased never leaving us, even when the corporeality has.

The Importance of Sacred Awe and Terror

If you have read my preceding “shadow” articles, you will have observed that the main thrust of my argument is that the monsters are not external apparitions, but rather unpleasant aspects of our psyche residing deep inside us. Despite this, I invoke the importance of the sacred sense of awe and terror that the monsters inspire.

By being more observant and conscious of this fear, we might think twice about eradicating or killing the monster, or ghost, when we come face to face with it. In my previous essays, I have argued that suppressing or destroying monsters—the perceived enemy, or threat of evil—often achieves the opposite of the desired effect. It causes it to return ten-fold, in a form more monstrous and complicated than ever.

Can we learn to live with our monsters and our ghosts? Can we learn from them, instead of immediately finding a way to eliminate them? We will never be whole; we will always be fractured in some way. That is the wisdom of myth. It teaches us that destruction is always around the corner; and that life is circular. It doesn’t mean permitting all forms of “evil” to do their will unto the next set of victims falling prey to its wrath. We will fight to conquer it. We fight for life, and for love.

It is undeniable that we are enthusiastic about ghost stories, horror movies, collective hysteria about monsters, and conspiracy theories. Tarot and the occult have made a resurgence in the West in an age where we are learning to distrust religion and church doctrine. Being sceptical about everything is a new type of doctrine: atheism is a new religion. Do we become zealous about believing in nothing? Is a belief in what cannot be seen, or currently proven by science, irrational, ridiculous, even “feminised”? Critical thinking is a gift of the modern age, but it also sanitises and simplifies collective truisms that we always knew.

Mythology and the old stories teach us what we refuse to believe now, that life is full of inconsistencies, unfairness, pain, and tragedy. The Pagan gods were vengeful, chaotic, and sex-crazed. Even in a supposed “post-religious” society we cannot and do not accept these things about human nature. We believe politics, democracy, and justice will allow us to see reason. If there is no hell, heaven, or purgatory, we will create our own version of it on earth. We will judge people based on collective societal mores that are based on egalitarian, democratic principles. These principles will be controlled by news outlets, or social media owned by large corporations—or just Elon Musk— ensuring that “democratic, free speech” prevails.

Currently, I see more rationality in mythology and ghost stories than in how public information is controlled. Monsters reveal the truth to us—the truth of our unconscious desires and fears. This is how we end up back again, full circle, to the shadow self. Western ideology means that we repress ourselves from shadow desire and that we are not able to accept the reality of immorality, chaos, destruction, or darkness.

If we did, we might question the value of accruing wealth, as that is so often linked to “goodness”, “safety”, “surety” in society, or even being a better, more valued citizen. If we allow ourselves to truly see the monsters and ghosts living amongst us, we might start living, and then we might stop striving for a better world, where we are finally permitted to love. We would be able to see truthfully: that we can love here, as we are, in our world of ghosts, monsters, and shadows.

P.s. Please support my career as a writer by liking, commenting, and fuelling my coffee (or cost of living) funds. Thank you so much for reading.