I want time to know he doesn’t scare me.

But he does.

Who doesn’t have a battle with time?

Since Einstein’s theory of relativity, theorists have argued that time as we know it doesn’t exist, though this has been hotly contested by some physicists in the scientific community.

What remains from this debate is that time as a fixed concept is refutable. Yet, the discord in the scientific community and our modern, rather rigid understanding of time means that we must put on a philosopher’s hat to reappraise it.

Ever since I became aware of the notion that time could be subjective, I began to redefine its role in my own life. I realised that denying its existence was impractical. The companies that pay our wages are not interested in the debate, and we must clock in and clock out on their time; meet deadlines. And with globalisation, time is increasingly more standardised. So how do we challenge our relationship with time when survival predicates that we must participate in this global economy?

The problem, as I see it, is that continuously dividing up time forces us to perpetually evaluate ourselves according to what we should have “achieved” within small blocks of time. Keeping abreast of short term goals can improve our general wellbeing. Making sure we have eaten three or so healthy meals a day, greeted another person or done some physical activity is good for us.

But the obsessive monitoring of how we spend our time means that long-term life projects, which should flow and grow naturally, are controlled and forced to the point that they are unenjoyable, and often, unsuccessful. What should be part of the directionless surprise of living – finding your talents in certain areas; making friends or meeting lovers – becomes a joyless pursuit of achieving or conquering. And when you have conquered your objective, you “maximise” your time with it, rather than experiencing it.

A lot of people idly wish for more hours in the day, but I don’t.

I want to live without direction. Because I’ve realised that when I do, I will experience, ergo enjoy life. I want to let go of the collective nightmare of time we have created, finger by finger. But that’s easier said than done. Every morning before the thought-flood of doom arrives I take a breath, reminding myself not to rush. I remember a story oft-repeated phrase in Tara Brach’s podcast which discusses meditation and Buddhist thought from her perspective as a trained psychologist. It is a story about a woman she knew, a mother who had recently given birth and had terminal cancer. “I have no time to rush”, she would repeat to herself, as she watched her baby grow, knowing she had so little time left with her child.

But this is an exceptional, and tragic circumstance. Most of us are running around like headless chickens, not because we want to be, but because we have to pay bills. And this frantic energy bleeds into “leisure time” if you’re lucky enough to have it. We must “make the most” of every experience, so that our time off is worth it. Time is undeniably and inextricably tied up with “productivity”, and how we utilise it to make money. Societally we are judged by the abundance of our productivity or the absence of it.

I’ve recently arrived back from two weeks teaching English on a canal boat, or more precisely, “a narrowboat”. It is owned by a friend who runs a language school on the boat every summer. Outside of the lessons everyone participates in the everyday tasks of the narrowboat; steering, mooring, opening and closing the canal locks, filling up the water tank, washing up (there is someone employed to cook the meals), and even the unpleasant task of pumping out the sewage. When I wasn’t teaching or doing these activities, I spent my time eating, playing guitar, sketching, reading, eating, writing, and eating.

The job wasn’t well paid but it had many perks. Evenings were spent visiting the characterful canal (or near-to-the-canal) pubs of middle England. There was Mad O’Rourke’s Pie Factory, a pub replete with quirky signs, named after a successful pie factory owner who reportedly had an affair with the raunchy famine queen Victoria, a frequent visitor of the factory.

The reason I was able to partake in so many of these activities, with time to spare for my own pursuits, was because I didn’t have a phone. Admittedly, my phone and I were parted against my will. One morning, as I climbed up onto the roof of the boat to meditate, my phone fell out of my pocket and into the canal. I huffed and puffed and then got into the canal to fish it out after the captain convinced me that it was salvageable. Waist-deep in, I only had to rummage around a bit before I found it, squealing and yelling.

The phone never recovered from its sludgy canal bath. I was mostly concerned about losing my videos. I had been uploading cute little films about canal boat life to instagram. And despite the frantic activity of the first few days I had somehow managed to find the time to write something, typing it furiously into my phone, publishing it on Medium in a canalside pub.

A strange pitfall of being a creative person is the maddening temptation to turn every experience into some kind of art.

On some occasions it’s a lifesaver, especially when you are overwhelmed. It is an excuse to disengage and channel frustration into catharsis. At other times, you do it because you are desperately challenging society’s impression that you are a good-for-nothing labour shirker, elevating what is merely a hobby into a grandiose pursuit. Many of my artist friends suffer from this guilt, and will swing wildly between churning out creative work through sleepless nights, burning the candle at both ends, then excessively sleeping as the body recovers in the days following.

This is what I am currently experiencing, desperately trying to return to the rhythm of normal life after sleeping an average of three hours a night on the boat. I tossed and turned in the sleeping bag acquired from the captain’s time in communist GDR East Berlin (as much of the equipment on the boat is). Each night I would hear eight other people tossing and turning, snoring and farting along the length of the large but narrow boat. Fast forward to now, and I am living in London in my mum’s spare room looking for work and getting interviewed for jobs that don’t meet the London minimum wage.

I came to London because there is no English teaching work during the Andalusian summer, and the pay is so low that it doesn’t cover summer expenses. Not to mention that the heat is unbearable there. A friend of mine lured me over to London with the promise of day work in the film industry, herding extras and mounting sets. As soon as I arrived the writer’s strike was announced, leaving thousands of people here in the UK jobless and stranded.

There hasn’t been a great deal of publicity about it. As my mate told me, it’s likely due to the misconception that only writers and actors in LA with fat pay cheques are affected. But huge amounts of people on the lower end of the economic scale are affected too. There are no solidarity funds or soup kitchens either, something that even penniless communities during the miner’s strike in the north of England managed to summon up in Thatcher’s Britain. So I’m under the dazzling lights of one of the world’s capitals and it’s looking a bit grim. I’m sleeping a lot and drinking endless cups of tea.

I am undergoing a huge amount of change in my life, and I remember it’s normal to struggle to find a good sleep, eat and exercise routine, or make decisions when you are in this situation. So I forgive myself and continue writing and making things, even if I don’t have the presence of mind yet to find a way to be remunerated properly for this work. The boat was a kind of bliss though, and it made a huge impression on me. It jolted me out of a stupor I didn’t comprehend I had been in. So when my phone fell in the water I lost all sense of time and it was beautiful.

Amongst the hectic activity I serenaded members of the boat, singing Dirty Old Town to ominous-looking black bullocks in a field beside the canal. I ran up and down locks in bare feet, wading through biblical floods of water we had unleashed in Wolverhampton due to a problem with a faulty, dry lock. On that particular occasion, I remember seeing men who had been fishing in the canal retreat to the edge of the towpath as the water overflowed.

One of my lovely students brought me rosemary tea that his partner had picked in their French garden, and also a sugary jam doughnut. I saw the sun set on a wonky bridge as I cursed the other people on the boat, people who I’d got to know so intensely over the two week period, the majority of whom I’d never met before. I loved them all and got irritated as I would with family members.

Time stopped as we discussed politics, Britishness and Englishness and Scottishness and Irishness (I was trying to explain the diversity of what Englishness is as a teacher, and why grammar isn’t that important). We exchanged rebel songs from around Europe. We talked about the climate crisis with a soft seriousness and none of the denial, shrugs or pearl clutching that so often accompanies this subject. We ate foraged canal nettle soup, and meadowsweet custard. We shared jokes and laughed and cried.

Since the pandemic, intense human emotions and reactions between unfamiliar people have frightened me. I was amazed to truly be able to live them, not feeling abandoned or judged for having had them. I witnessed similar moments in other people and processed it naturally without accusing them of narcissism or psychopathy. I heard night time chats I wasn’t supposed to hear over the berth of my tiny little bunk bed. Meanwhile, the canal boat, powered mostly by solar panels, and it being a rather wet, dull summer in England, chugged along at 1 mile per hour.

Our colonisation and sequestering of time allows us to divide it into sections, of whom or how we might choose to spend it.

In reality it leaks out and overflows like the locks of the canal, because it has to, in order for us to continue our journey. The first time I drove the boat alone I listened to a mindfulness podcast. After the death of my phone, I stared into the distance, doing mindfulness unaided. I listened to the water, the birds and noticed the different consistencies, when the water might be getting shallow, or weeds getting trapped in the propeller. I noticed what my body felt like. And none of this is magical, though we evangelise about it in clickbaity articles and reels on instagram. In reality, this is what being alive should be.

Being on the boat felt good not because it was a relaxing holiday, but because it was hectic and messy and human. It reignited my spark and desire to labour for a good, just and harmonious cause. Living in London had burnt me out, making ends meet, working in the arts and campaigning for social justice, whilst living in precarious housing situations. After moving to Andalusia, and seeing that exploitation and job conditions there were far worse, I had got bitter about the concept of “labour and productivity”. Yet the slowness of life in Andalusia, coupled with the fact that I had sun, sea, and affordable fruit and vegetables, had restored me. I didn’t have money, but I had presence of mind, and that felt more meaningful. I was living.

However, my arts practice and “career” in theatre and education came to a grinding halt, and I worked hard to overcome the fear that I would disappear into a black hole of nothingness due to my lack of “productivity”. The fear was unfounded as I wrote, practised music, started a band, a choir, continued my social justice activities, made audiovisual poems and flamenco documentaries.

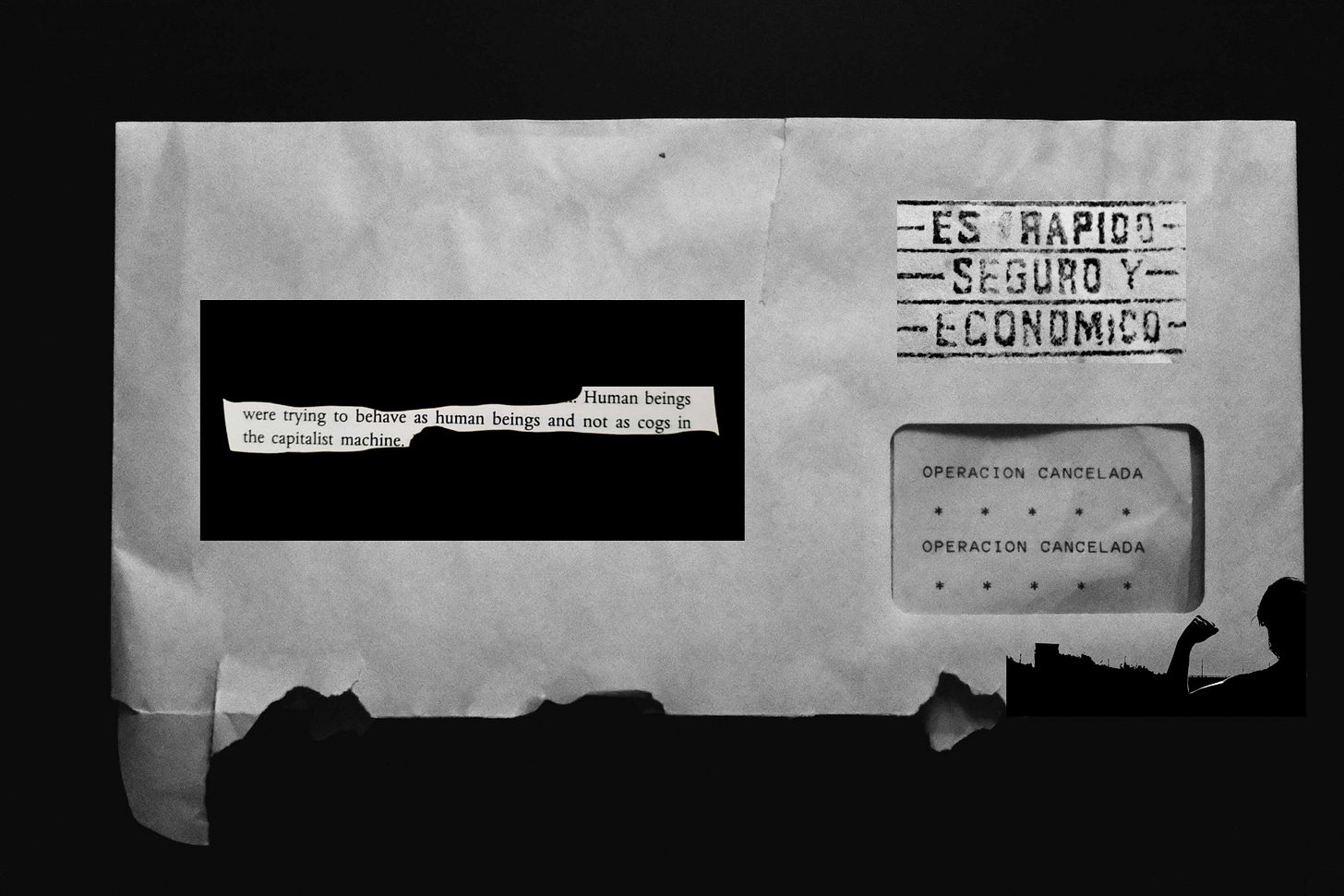

Eventually I felt proud that I wasn’t participating in the capitalist system, but it did leave me in a precarious situation where I was often reliant on others to support me (who were reliant on that system anyway). I rationalised that the people supporting me were helping me to support others, and that the support I gave to others, being outside of the exchange of monetary value, was precious and important. And I do believe this is important, in a society obsessed and fearful about money. Yet something felt unbalanced. My abstinence from the world of productivity began to feel nihilistic. I began to doubt if my small, careful actions would ever really make a difference.

I believe that small, local actions can and will make a massive difference.

Overwhelming ourselves to the point of inertia with thoughts of nuclear warfare and large immoral corporations that pollute the planet is tempting. Unequivocally, it’s important not to forget this information. But let us not forget the importance of smallness. A small group of people or even an individual initiating an action has the power to create a ripple effect of great change. Look at Standing Rock, The Easter Rising of 1916 or the small acts of truancy begun by Greta Thunberg to protest climate ennui.

However, to start these ripple effects we must get a bit dirty, or stand elbow to elbow in close proximity with others. Even if like me, you are introverted and sensitive, and being surrounded by a lot of people can be taxing or harmful to your wellbeing. In my previous newsletters I have talked at length about all the techniques and coping mechanisms I use to armour myself against this.

Hannah Arendt, in her essay, Labour, Work, Action, makes a distinction between work and labour, following from John Locke, who distinguished the “the work of our hands” versus “the work of the body”. Arendt connects “labour” to the natural, biological processes of our body (it is the word we use for giving birth), referring to it as a repetitive activity, which follows the cycle of life and the circular movement of our bodily functions. Whereas “work” is an activity completed with the hands (though nowadays these hands are usually manipulating technology) to create and multiply objects, or products, exploiting the earth’s natural resources to do so. “Work” is finite, not cyclical, and finishes as soon as the product is made.

Arendt argued:

“The blessing of life as a whole, inherent in labour, can never be found in work and should not be mistaken for the inevitably brief spell of joy that follows accomplishment and attends achievement.”

It’s a compelling hypothesis, and caused me to reframe the pessimism I felt about the subject of “work” and productivity. The idea that, on completion of an action in exchange for monetary remuneration (or even activities completed in order to strengthen your CV or boost your social media account), all one ever does is make a small group of people richer, or pollute the planet further. Yet, by creating a distinction between “work” and “labour”, Arendt’s argument helped me to understand what I was missing. I wanted to toil and get my hands dirty, but it was the cyclical, biological, action of labour I was craving. I guess that’s why we talk about “the fruits of labour” and “not the fruits of my job”.

Arendt explains this better than I when she writes:

“Labouring is the only way we can also remain and swing contentedly in nature’s prescribed cycle, toiling and resting, labouring and consuming, with the same happy and purposeless regularity with which day and night, life and death follow each other.”

I believe it’s the purposelessness of toil which ultimately helps us find purpose. We collaborate and get mucky and exhausted because that’s what we’re supposed to do. Labour, unlike work, doesn’t exclude others. We all have diverse capacities, mental and bodily limitations. Work means that something must be done a certain way, replicated and multiplied exactly. Labour is merely repetitive. It doesn’t require any particular type of strength or precise way of doing things.

When a crew member of the canal boat crew was able to run ahead or pull the boat along using their body weight, other members could ramble alongside the canal shouting encouragement and picking berries to make jam with later. All labour is worthwhile and interconnected. Labour is as inconsistent and inconsequential as life itself. Being on the boat felt spiritually fulfilling. My labour was necessary to the crew but inconsequential to some oligarch or media mogul. That made me feel alive again.

Yet I am back in the city and I return to the continuous struggle with time.

I am not sure I’ll conquer it alone.

Is it possible to shake off the chains of our limiting understanding of “time versus labour” through collaboration with others?

The more I connect with others, the more I realise that my ideas don’t exist in a vacuum. The other day I was in a hipster coffee shop drinking an oat flat white I couldn’t afford. I overheard the woman behind me saying that capitalism had deceived us into believing that we needed so many things when really we needed nothing. I was sketching, which is a new habit I picked up again after losing my phone. I turned around and told her I agreed with her, and she said “thank you”.

Originally I had found her shouting about capitalism a bit obnoxious and irritating, disrupting the peaceful slice of time I'd decided to buy for myself with an extortionate London coffee. But we connected and smiled at each other. Her voice indicated she was from somewhere in Eastern Europe though I couldn’t place where. We had traversed different parts of the world and were there together, in one of the most competitive economies of the globe, poopoo-ing capitalism. The grumpy hipster staff stopped rolling the dough of their coveted cinnamon buns to silently agree with us.

Referring to the messy web of interchange and human existence, Hannah Arendt said,

“the real story in which we are engaged as long as we live has no visible or invisible maker because it is not made.”

Or, to use a commonly used quote, originally from the writer Alan Saunders, though it’s often attributed to John Lennon:

“Life is what happens to you while you're busy making other plans”.

My interpretation is that to live our life naturally; to labour and feel the satisfaction of that labour, we have to accept whatever story unfolds for us. Manufacturing life, pushing our body into rhythms and timeframes that feel unnatural, is merely a replication of industry or “work”. And it is for precisely this reason I believe so many of us suffer, and why depression rates are so high in rich nations.

This is not to say “poor rich folk”, but to question why we glorify extreme productivity. If richer exploiting nations can’t be convinced that this way of life is untenable by the undeniable fact that they are destroying the planet, ecosystem and habitability of exploited nations, then perhaps holding up a mirror to their own suffering will. The rate at which we are expected to work is unnatural. We may have opposable thumbs but we are no better than any other species. We eat, have sex, sometimes give birth, then we sleep. Then we die. And it starts again. That’s all it is. A beautiful simple cycle.

I don’t want it to take me being stuck in a magical forest with a band of misfits somewhere near the Black Country (former mining villages), to think, ah, this is my paltry slice of time to commune with nature! Or commune with people. Or be okay with dirty canal feet and not care about having a shower or my oil stained garments. I want this everyday and I want it for all of us.

One morning whilst on the boat, I went for a run and lost sight of the boat after diverging from the canal path and running through the town. It turned out the boat was slowly creeping down a long tunnel. I was dying for a piss, and I was tired and hungry. It had started to rain. I panicked. I didn’t have my phone and imagined being stuck there for hours. Then I heard the motley crew of my gang singing their strange choral arrangements of political songs in different languages. It echoed phantasmally through the tunnel. It sounded as if they were echoing through the centuries. Though I was angry at the captain (always vague in his directions of where the boat was headed each time I went for a run) I chuckled and felt warm. We could have been in any strata of time at that moment.

I remembered that getting lost is part of life’s story. Asking people where to go without google maps, hoping blindly that someone might turn up when they said they would. I cherish that and pray for its return, because without it life is already written. And then what’s the point?

On stories, Hannah Arendt wrote:

“It is because of this already existing web of human relationships with its conflicting wills and intentions that action almost never achieves its purpose. And it is also because of this medium and the attendant quality of unpredictability that action always produces stories, with or without intentions, as naturally as fabrication produces tangible things.”

If I don’t let life happen to me, I’ll never be able to write stories, and you’d never be able to read them.

Other work:

I’ve been writing a lot of poetry and I plan to get better at uploading it to my vimeo and sharing it. You can see some of what I do on my instagram, or here on vimeo.

I recently published my first audiovisual poem in Spanish Castilian. Here it is:

P.s. If you like what I do, please consider tipping me, which helps with writing submissions. Thank you!