In my last piece, I wrote about the highs and lows of my Vipassana experience, its teachings and the doubts that remained with me. But I excluded to mention the seminal moment of the retreat. Though it was an understated moment, it is vivid in my mind.

The event took place in the garden of the retreat. It was a sharp, frosty day and a persistent wind blew. I had sat down on a plastic garden chair, facing the sun, which, despite the frost, beamed a piercing winter light. It was then that I caught sight of an “orb weaver” spider, casting its web into the wind. The sun illuminated the gleam of its silken thread, inches away from my face. It had launched its web on to the baby birch beside me, its fragile body flailing against the wind, while its spindly but powerful legs worked furiously to propel itself towards the tree.

After what seemed like minutes, but must have only been seconds, the tiny but courageous being lost the struggle. The thread broke and it hurtled off to its next spot, where it would begin the same dance. Its heroism was touching to behold. I had, most likely, been sitting there feeling sorry for myself. Why me? Why did all the things I wanted get taken from me? For I had come to the retreat carrying a deep well of grief inside, and all I could feel in my heart was loss.

After witnessing the spider, my self-pity turned into gratitude, which flowed down my cheeks. Even though the spider had not been able to attach itself to the tree, its perceived “failure” was but a blip in the daily dance life of an orb weaver. The orb weaver wouldn’t now be drooping on a blade of grass somewhere bewailing the loss of its attachment to the beech tree. It would be casting its web out elsewhere. And due to the wind, it had a busy day ahead.

It wasn’t the first encounter I’d had with an orb weaver. I am not a spider expert, and the only reason I identified it accurately was because one had landed on me only a couple of months before, on my birthday. I had been sitting in the backseat of a car when I noticed a brightly-coloured spider, almost golden in hue, crawling up my cardigan. In that period of my life, I had witnessed several spiders landing on me, and in 2024, had also decided that “gold” as well as red, were “my colours”.

I took the spider’s choice to land on me that day as significant. After nosing through spider identification charts and Wikipedia articles I was able to identify it as the common UK “orb weaver spider”. In doing so I came across a blog by Mark Sprinkle, which shared insights into the habits of the orb weaver, recounting a lecture by the poet, Suzanne Rhodes. In Sprinkle’s words, this is how Rhodes described the orb weaver’s behaviour:

An orb weaver begins her work by casting a multi/stranded line of silk far into the air, letting the wind carry it in an often considerable distance before it hits an upright object like a tree, a tall stalk of grass, or even a building. From this initial thread the spider begins to build the scaffolding for the rest of the web.

For Rhodes, this first arachnid ‘act of faith’ is very much like the way a poet must must begin a work by allowing her thoughts and sensibilities to focus on whatever happens to be out there in the natural and cultural world at the moment – essentially waiting on the spirit to take the lead by carrying the silk of her attention to where it needs to be attached. This is neither an unguided nor unconstrained sense of ‘inspiration’, but one that recognises the importance of waiting (rather than an immediate act of will) to creative acts like poetry–something not far from the kind of patience and observation practised by scientists in order to discern a specific approach to solving a problem in their fields, or even to recognise a problem in the first place.

Just beautiful. One could apply this to poetry, but also to the “acts of faith” we take in life. Sometimes we become attached to something, or someone, until the connection between us is blown away by a cruel wind. When we are separated from something, or what we wanted is seemingly “taken away from us”, we can veer from mourning its loss to cursing ourselves for getting attached in the first place. We should have known better. Why didn’t we know before this happened that it would be taken away from us? But rarely we can know.

That’s why I was so moved by the orb weaver’s act. Its bravery! I recognised my own bravery reflected in this delicate but robust creature. I thanked the spider for reminding me of myself. We are never stupid or deficient in trying, trusting, or taking risks. In fact, quite the opposite. That is the good news. The bad news is that we need to continue casting out those webs, taking those risks, and if we don’t, we aren’t truly living as we should.

Recently, I picked up another copy of the Bhagavad Gita, deciding to read it again more thoroughly. My interest peaked during the Oppenheimer movie mania. The Bhagavad Gita had been one of Oppenheimer’s favourite texts, and he had famously quoted it in a television interview, possibly to justify his part in the development of the atomic bomb. Or, perhaps to explain why he felt he didn’t have a choice in the matter.

[You can read about this and its relation to Shiva here.]

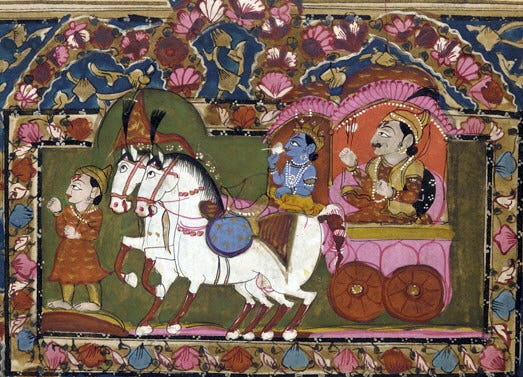

The story is as follows: Prince Arjuna is about to go into battle, accompanied by Krishna, who is an incarnation of Vishnu, but Arjuna is terrified, and understandably, is afraid of the moral repercussions of the impending mass slaughter. The text is mostly comprised of Krishna’s arguments as to why Arjun must do his duty and carry out his destiny as a man born into the class of warriors. The Bhagavad Gita has at times been criticised as a problematic clarion call to justify wars by religious zealots, but I believe that’s a misinterpretation. It’s more useful to understand the text as a metaphor for the inward journey.

At a time when I was feeling lost; with no clear sense of where to advance or retreat to, it was oddly comforting to read. As a writer, singer, poet and artist, I have often wished I had been born into the world with what “society” (or the capitalists consider) more “practical” skills. Or that I had the patience or wherewithal to work in a safe, office job, mostly so that I wouldn’t have to worry if I’d arrive at the end of the month or avoid the questioning stares of family members who still don’t understand why I couldn’t have just become a teacher (I tried! It didn’t work).

In the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna expounds on the intricacies of doing “thy work”, which could be understood as the actions we take in life. Following our destined path, and the idea of it being as a result of “effortless action” is a common idea in many spiritual teachings, such as Taoism, which directly translates from Chinese to “the way”. Yet how can our actions be effortless?

In the Gita, Krishna says to Arjuna:

Set thy heart upon thy work, but never on its reward. Work not for a reward; but never cease to do thy work.

Do thy work in the peace of Yoga, and, free from selfish desires, be not moved in success or in failure.

Work done for a reward is much lower than work done in the yoga of wisdom. Seek salvation in the yoga of wisdom. Seek salvation in the wisdom of reason. How poor those who work for a reward!

This echoes a quote I recently encountered in a French bookshop, picking a book up at random. The quote was by Lao Tze, a sixth-century philosopher known as the founder of Taoism. I sent the excerpt for translation to my mother and German stepdad (whose children are half-French), as we had started up a rather esoteric Whatsapp group discussing Taoist and Sufi texts. The text is as follows:

Who stands on tiptoes cannot stay standing up

Who takes double strides cannot walk

Who puts themselves before everyone's eyes is without light

Who gives themselves reason is without glory

Who boasts of their talents is without merit

Who takes pride in their success will not prevail

My mother rightly pointed out that the tone was excessively puritanical. Yet, as my stepdad countered, it is a welcome antidote to middle-class pomposity, the idea that one’s profession and work are the most important when many cohorts of society struggle to get their basic needs met. Surely housing for all, access to nutritious food and green spaces take precedence over accolades and clever titles?

But I digress, my takeaway from these stern spiritual teachings is that if you are doing what you are truly supposed to be doing, there is no need to bask in “glory”, to take pride, or seek external validation. We all know what it feels like to be in a job, relationship, or friendship that drains us, but when we do the work, or spend time with certain people and it feels natural or effortless, then we know we are on the right path.

Undoubtedly there is no harm in enjoying one’s own “success” (however one chooses to measure it) or feeling content about the good outcomes of one’s actions. I don’t believe that one has to be austere, nor emotionally removed from what one does. Quite the opposite. But personally, I take comfort in the idea that I do not choose the work I do, but the work has chosen me.

Why push and go somewhere that feels unnatural to you?

The orb weaver spider casts its web out to the wind, following and responding to the object it is attached to. There is an element of chance to the act, and the weather conditions will determine where its web lands. But there is a limitation of choices. The orb weaver web, whilst it can travel a considerable distance, cannot reach a tree in a forest thousands of miles away, and if it hits a moving target, or potential predator, the thread is likely to break, and the clever creature scuttles away.

The actions and choices we make are usually determined by proximity, and the practicalities of the conditions we live in. If we follow impractical fantasies, as most of us know, we are likely to suffer if we do not understand that our hopes are based on delusions. Therefore, like the orb weaver, we must take action to do our work but know the right time to act.

I spent most of my childhood escaping what I found was a painful reality, and I did this through novels. My fanciful imagination can make interesting, creative work, but also can cause me to suffer in my personal life. To correct this, I have recently found myself resistant to reading novels. Why would I want to escape into the delusions of the mind of a fictional character when I have my own to bear? Nowadays I am compelled to read memoirs (certain types: the types that are self-knowing in the fact that the narrator is unreliable), poetry, and spiritual texts that guide us towards seeing “truth”, and accepting things as they are.

I acknowledge that in my own writing I am the unreliable narrator, though I am grasping towards a sense of honesty and truth. I cannot confidently tell my readers how one knows when the right time to act is. We talk about “gut feelings”, but a confused person, or someone who uses escapism as a coping mechanism, will struggle to differentiate instinctive gut feelings from fear-based reactions.

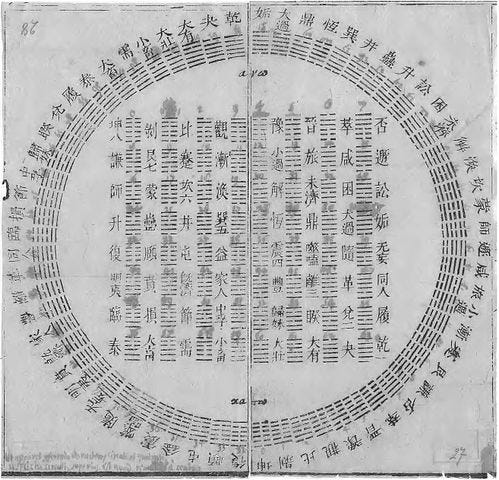

To know what actions are truly right for us takes time and intention. An unconventional tool that I have found helpful is the I Ching. The I Ching is an ancient divination manual used primarily in China between 1000 – 750 BC. In the 2nd century BC, the I Ching was the basis for divination practice for centuries across the Far East and the subject of scholarly commentary.

When I tell people about it, I say, essentially, it’s a gorgeous epic poem, and reading it is like receiving advice from millennia-old monks. It has sixty-four hexagrams, and traditionally, to cast a reading, yarrow sticks are used. A modern popular culture reference can be found in the character of Mary Malone in Phillip Pullman’s His Dark Materials. Ironically, Malone is a scientist who casts I Ching readings to navigate her way through different worlds in her quest for dust.

One of the most important hexagrams in the I Ching is hexagram number one, “Heaven” (Qian), which relates to the pure yang “masculine archetype” energy. It is about taking action but knowing when to take action:

When it is not favourable to advance, it is time to gather one’s strength, hold one’s faith, and stand steadfast waiting for the right time and proper situation. When the time is right to progress, one should stand guard against arrogance and rashness, making no move without careful thought and always keeping in mind that things that go beyond their extreme will alternate to their opposites.

When the time and situation are not suitable for one to move, one should have patience. On the other hand, when the time and circumstances are favourable for one to advance, one should not lose the opportunity. This is what the ancient sage meant: following the way of a superior person, always vitalising and advancing oneself.

Qian is counterbalanced by hexagram number two, “Earth”, or “Responding”, (Kun) which is pure yin energy, the epitome of the “feminine archetype”. It functions harmoniously with Qian, the yang energy. In the I Ching text interpreted by Taoist Master, Alfred Huang, he explains:

The ancient Chinese believed that too much yang and too little yin is too hard, without elasticity and likely to be broken. Too much yin and too little yang is too soft, without spirit and likely to become inert. Yin and yang must coordinate and support each other.

Yin is the most gentle and submissive; when put in motion, it is strong and firm.

Yin is the most quiet and still; when taking action, it is able to reach a definite goal.

Undeniably, The I Ching is rampant with gender stereotypes, but like the Bhagavad Gita, I interpret it symbolically. It is true that both qualities of yin and yang, if balanced in each of us, can be used to make better decisions or take more precise actions.

The orb weaver takes decisive action in casting its web as in Qian, but responds to wherever its thread has landed, as in Kun. Somewhere between the two states good decisions can be made. At different times of my life, I have had tendencies towards too much yang, and inevitably this has led to burnout. Arguably, the West is a rampantly yang-imbued culture. As a consequence of this, the task of advancing at the “favourable time” is complicated. Living in a culture of constant calls to action, overwhelm and over-communication makes it difficult to know whether the action one takes comes from within, or is influenced by exterior forces. On the other hand, I have periods of yin energy overwhelm, and in lieu of taking any action, have grown still and stagnant. I would relate my excessive yin phases to passing through depression.

The Gita says:

Not by refraining from action does man attain freedom from action. Not by mere renunciation does he attain supreme perfection.

For not even for a moment can a man be without action. Helplessly are all driven to action by the forces born of nature.

He who withdraws himself from actions, but ponders on their pleasures in his heart, he is under a delusion and is a false follower of the path.

Action is greater than inaction: perform therefore thy task in life. Even the life of the body could not be if there were no action.

The world is in the bonds of action, unless the action is consecration. Let thy actions then be pure, free from the bonds of desire.

These are hard words, and when we see “man” mentioned, we can take it to mean humankind. Yet reading this part gave me a jumpstart during a particularly yin phase of my life. I could sit and meditate, read the spiritual texts all day, but that would not get me closer to where I was supposed to be. Like Arjuna, I was terrified about the consequences that my actions could have, although I was fortunate that I didn’t have to go into battle. Prolonged introspective yin periods can indeed cause an imbalance, but they can also help us, particularly after a period of excessive yang energy: going too hard and fast without considering the consequences.

I realised that my actions didn't have to be “correct”, or particularly meaningful. Every step I took didn’t have to be exponentially analysed. Neither did it have to be mindless, or reckless.

As Antonio Machado, the Sevillian poet wrote:

Caminante, son tus huellas

el camino y nada más;

caminante, no hay camino,

se hace camino al andar.

Al andar se hace camino,

y al volver la vista atrás

se ve la senda que nunca

se ha de volver a pisar.

Caminante, no hay camino,

sino estelas en la mar.

English Translation:

Walker, your footprints

are the path and nothing more;

walker, there is no path,

the path is made by walking.

The path is made by walking,

and when you look back

you see the path that

you will never walk again.

Walker, there is no path,

only ripples in the sea.

Caminante. Just walk. Perhaps your actions won’t lead to the result you desire, but if you work to let go of that desire, then the actions will be “right”, whatever they are. They will at the very least reveal a truth that you did not previously see.

I Could Read the Sky is a fictional memoir written by Timothy O’Grady, collected from the testimonies of various Irish immigrants. I love it for its presentness; its lack of story-ness; the non-temporality and immediacy of the reflections of the narrator. At some point the narrator says:

I thought I had a future too but I could not see it. It was in the things I lifted and carried and in what I was given for doing it. This was a future that flickered and darkened whenever I tried to look at it.

That’s how the book feels, and that’s how life feels when we aren’t stuck. The picking up and the putting down of things. The noticing of the moment we’re in, rather than the endless reflection on whether we should have picked that box up at that moment or not. Did we truly desire that box to be picked up at the time that it was? Well, does it matter?

These spiritual texts sternly advise us to be free from desire. This is a seemingly unsurmountable feat, yet it is not impossible to target problem areas. Through intensive, gruelling inner work we can leave behind addictions, and toxic relationships. What is impossible, as humans, is detaching from our emotions. We are not like the orb weavers, who are evolutionarily programmed differently.

Many of the spiritual paths urge us to live “equanimously”: stepping aside from our grief and sorrow, observing it, although not repressing it. This is what the Vipassana course trains us to do. Undeniably, it helps. I returned from my retreat feeling cleaner inside. Yet, in the chaos of everyday life, it felt impossible to continue in the same way. The rigorous practice of Vipassana did not feel grounded in the reality of my daily experience as a human who could not live like a monk.

Quite simply, sometimes we will get stuck in our grief.

And at times we will not be able to move on and take action. Because we are a hive of strong emotions: anger, sorrow, jealousy. And if we do not allow ourselves to feel, we are numb and repressed. This is why it is our species, and not the orb weavers, that are destroying the planet, killing each other needlessly, with mindless, cruel wars. But we cannot escape ourselves. We must work with what we have, and the less we repress ourselves, in theory, the less ill feeling we have towards ourselves and fellow humans.

This is why I like the approach of the Sufis, who recognise that even when we hope for balance; harmoniousness; and a life not ruled so brutally by our desires: we do love, we do grieve and we do suffer, and this is part of the human experience.

Rumi wrote:

I cure my pain with suffering,

And make my work easier with patience.

I pull the foot of my soul out of the mud,

And bequeath my heart and soul to lovers.

I am a moth burned in the candle of eternity,

Serving the royal candle of the king.

I invite love into my burned heart,

Having but one heart to sacrifice for love.

If the lower self is like a cat that meows,

I know how to lure that cat into a sack.

Whoever is sadly shaking his head,

I pull him into a circle and make him whirl.

Since sadness comes from not having love,

I make his soul fall in love with love itself.

What is love? Absolute thirst.

I try to speak about the fountain of life.

Since I cannot find the words, I remain silent.

Whatever I cannot put into words, I do.

[Rumi, Unseen Poems: Everyman’s Pocket Library, 2019]

I love reading Rumi, because he continuously tells me that it’s okay to feel terrible. It’s human that my heart burns. Sometimes loving yields fragrant rose gardens, but it also invites difficult feelings, such as thirst, and it makes us suffer. But what do we do? At some point, we whirl like dervishes, and we put our mewling inferior selves away into the cat sack. Through intention, we love, feeling the joy and expansiveness of it. We pick up and lift the boxes. We put them down. We do not wait for the fragrance of the rose garden to come to us. We find it, and we create our own. If you long for a rose garden, find a way to plant one.

I can see this contrast and dance of human emotion in the songs of Violeta Parra. In “La Jardinera” she sings about cultivating a beautiful garden to forget someone, that the flowers will be her nurses. Parra’s loving compassion is evident in the lines:

And if for some reason I leave

Before you repent,

You will inherit these flowers,

Come and cure yourself with them

Contrast this with the bitter lyrics of “Maldigo del Alto Cielo” (I Curse from the High Sky):

I curse, from the high sky, the star with its reflection

I curse, the tiles, flashes of the stream

I curse, from the low ground, the stone with its outline

I curse the fire of the oven because my soul is in mourning

I curse the statutes of time with its 'suffocating'

How great will be my pain!

And in “Gracias a la Vida”, the last song she wrote before she died, she sings:

Thanks to life, which has given me so much

It has given me laughter and it has given me tears

So, I distinguish happiness from sorrow

The two elements that make up my song

And your song is the same song

And the song of everybody is my song too

The most spiritual words are the ones that allow us to experience every bitter and beautiful hue of emotion that resides in us. Our emotions are the invisible threads cast out, attached to things and people that we cannot see. They teach us something. We do not need these threads to be visible to know that they exist.

I’ll give you an example: for some years now, I would say, ever since I began to heal, I have felt the presence of my dead grandmother. She died when I was one year old, and she had Alzheimer's, so I never truly met her. Yet she is so vivid to me. She was short, petite, jolly, and kind. She always saw the best in everyone. She loved to sing and dance.

Even though the family was poor and she had six mouths to feed she always kept faith that they were going to be alright. And they were alright in the end. My great Uncle Billy, who is a priest, always said that if he could have, he would have canonized her. I can feel the energy of her near me, fizzing, attentive, always busy but never too busy for a chat. I can see parts of me in her, and when I am feeling bitter, it helps to remember that silken thread between her and me.

How can one explain this proximity? Because when I talk about objects needing to be proximate for a web to exist between you and the object, or person, I don’t mean physical closeness. The webs we cast transcend space and time, and in that sense, we are never alone, nor unattached, though it may feel like it at times.

I want to thank my grandma, Mary Kelly, for always seeing the best in life, even when it was hard, and for always having faith.

P.S. I now only make money from writing, singing, and creative workshops (i.e. little). I’ve decided to dedicate more time to writing. If you like what I do, and you’d like me to publish more, please consider supporting me. Thank you for reading!